31st Exeter Gulf Conference on :

Zones of Theory in the Study of Yemen

I’m glad to be here. It’s been six years now that I have been

completely out of touch with the Academia, so I really want to

thank the committee for their patience, and especially Claire

Beaugrand for encouraging me.

I am here to share with you an ethnographic research in a tiny little piece of urban fabric, to which I dedicated more than ten years of my life, from 2003 to 2013.

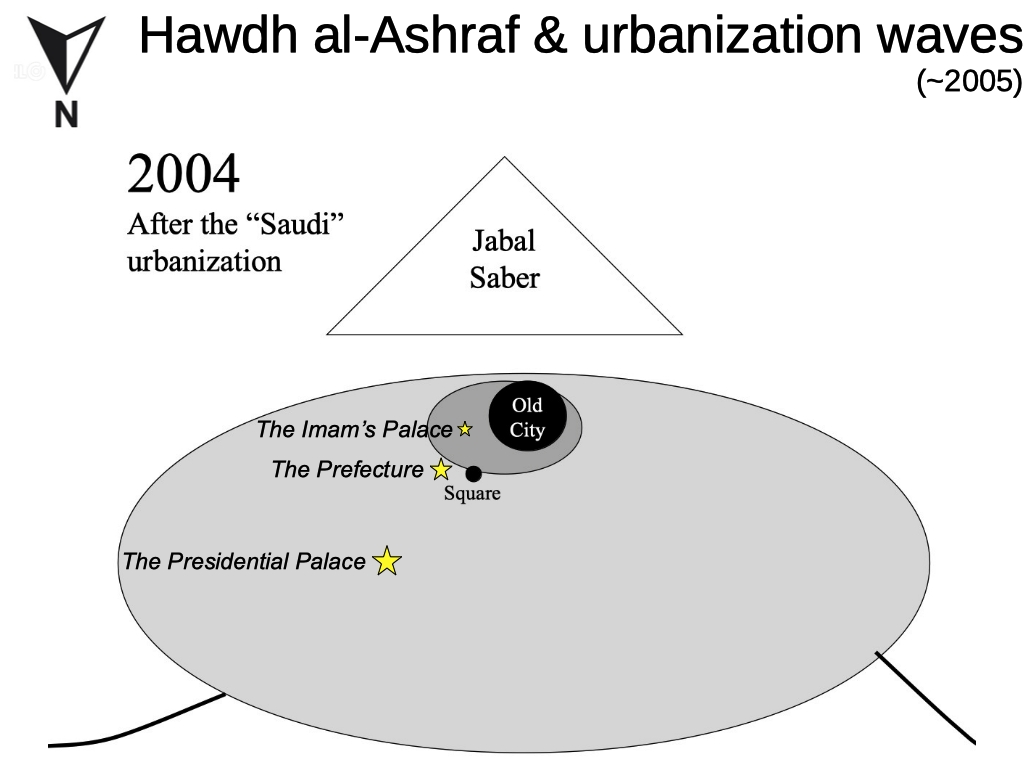

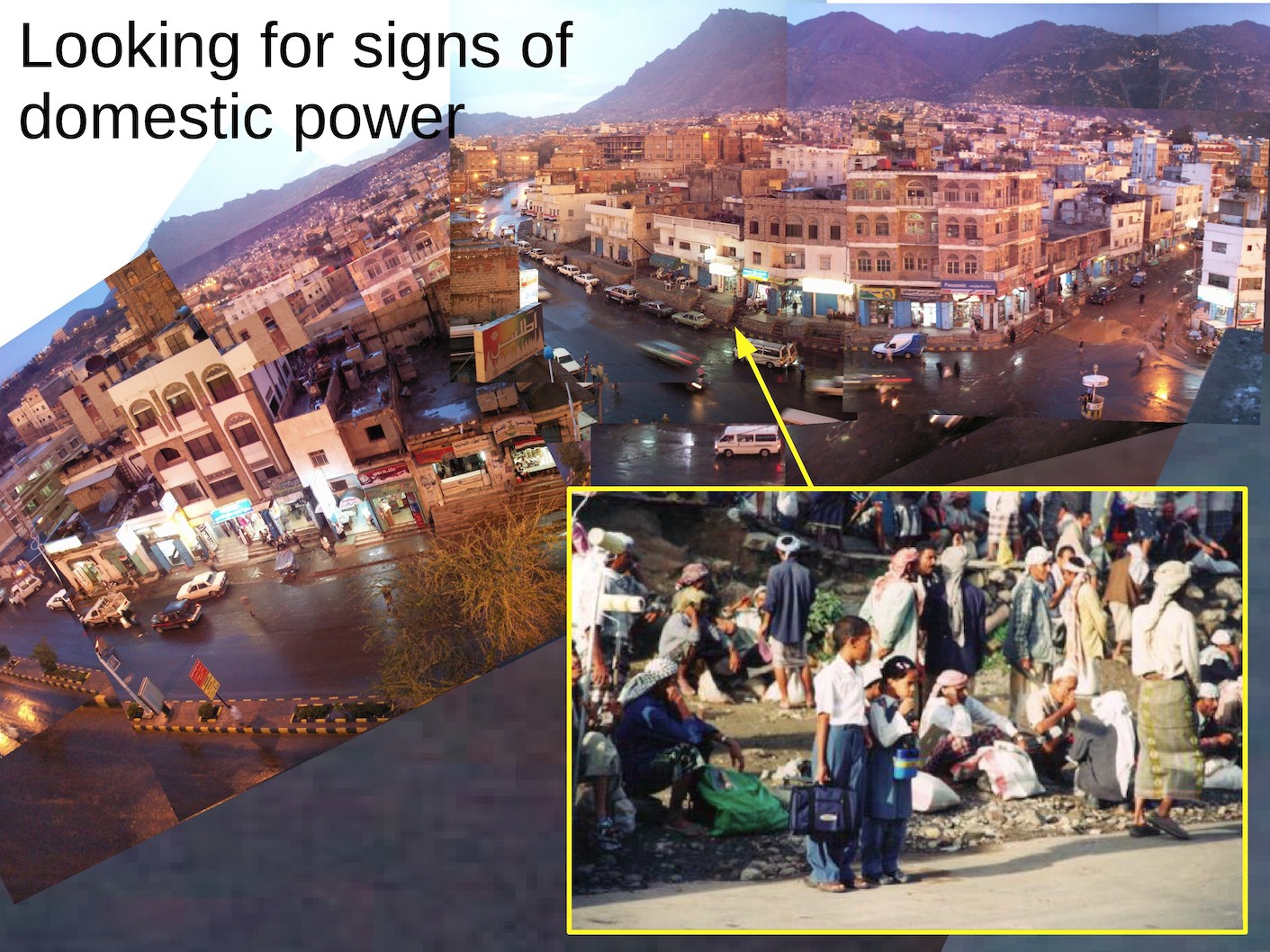

Hawdh al-Ashraf is one of the most famous square in Taiz, at the

entrance of the modern city. You have a souk there, and a traffic

hub connecting travelers nation-wide, all this coexisting with

residential areas.

In the days of the imam, Hawdh al-Ashraf was just a station for

camels outside the walls of the city.

The Prefecture was built there in the first years after the

Revolution.

Then the city continued to expand, as migrations to Gulf countries

brought money. The Presidential Palace built by Ali Saleh is

located further away on the road coming from Sanaa - a place where

he supposedly stored a large amount of weaponry…

Since 2015, this whole area has become the main hotspot in the

battle for Taiz, now guarded by landmines and snippers. And of

course, no cars arrive in Hawdh al-Ashraf anymore.

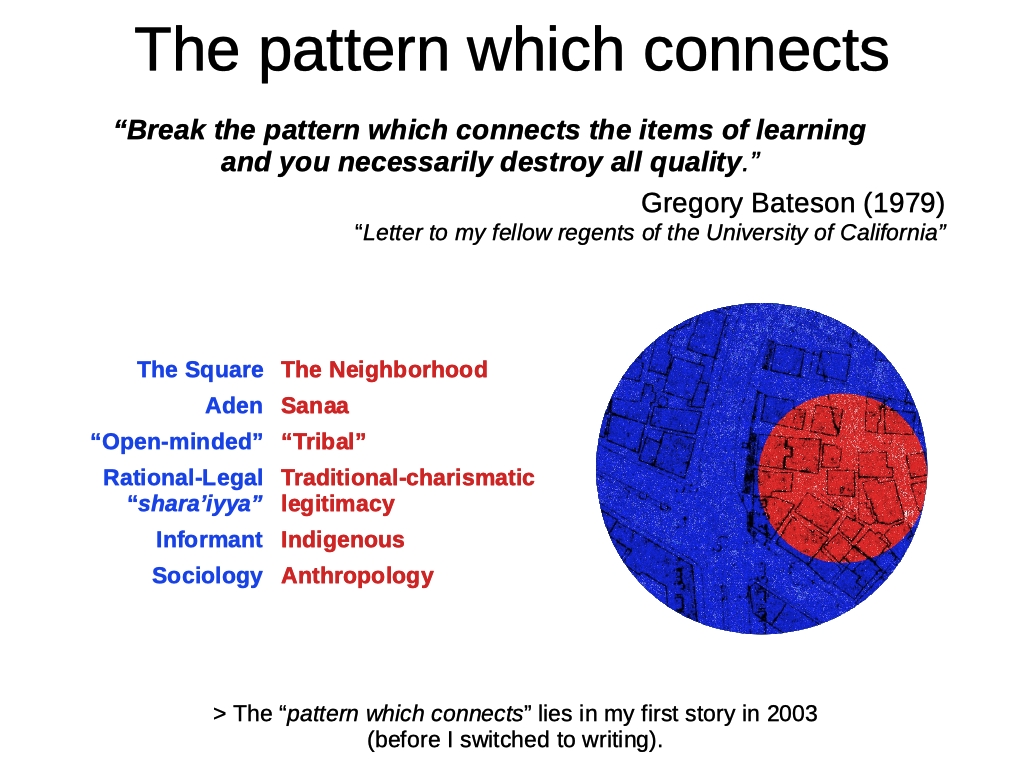

That is where I landed in 2003, for my first three months of

ethnographic immersion into Yemeni society. And it is quite

ironic, because my first memoir described exactly the same

cleavage : a little “civil war” between ashâb al-hâra wa

ashâb al-gawla, the people of the Neighborhood and the

people of the Square.

The people that I met here and there didn’t display the same

values, and often expressed contrasted viewpoints on political

issues. To put it short, the people of the neighborhood were

“tribal” : they were obsessed with questions of honor,

domesticity and political loyalty. Whereas people on the square,

both shopkeepers and students who hung out there, seemed much more

“open-minded” and industrious people. They answered freely to any

question that I raised, and seemed to be motivated by a

“progressive” political agenda. In other words, these were with

“Sanaa”, and these were with “Aden”. Never dit I infer however

that Yemen was about to collapse into a civil war…

Here, it is worth citing a famous sentence by British

anthropologist Gregory Bateson:

“Break the pattern which connects the items of learning and you necessarily destroy all quality.”

- My first interlocutors in Taiz were from the university. I lived with the secretary of the French department : a former student from Qadas who grew up in the village, and then held a shop in Hawdh Al-Ashraf while he attended university. For him, this was the only place in Taiz that felt like home, so he quickly took me there, and introduced me to local shopkeepers that he knew.

- And then I was invited to the wedding of an another French teacher who worked actually in Aden, in that precise neighborhood. There, I met a person who seemed superiorly intelligent. His name was Ziad, and he had just graduated in financial mathematics, ranking first in the whole university. We started to have wild philosophical discussions, and in the following weeks he gradually encouraged his young neighbors to interact with me.

It happened that Ziad came from the local family who had connections to the regime. His maternal grand father chose to move out from the old city and settle here, right below the walls of the Prefecture. Ziad and his older brother Nabil had been charismatic leaders in their youth. Nabil now worked as the chief of the central souk police (in the downtown/markazi sector), while Ziad was to become an accountant in big Yemeni industrial groups. But what kept me attached to him was his “intelligence”… Ziad did not behave with me as if I was the teacher, rather he gave me intellectual hospitality. As a former student in physics myself, this kind of scientific comradeship was clearly what I was looking for in Taiz, the city of learning.

And that was the origin of my “two-social-class” model. People in the neighborhood behaved very differently, because my relationship with Ziad was very different! And the Yemenis noticed of course, even though they did not understand the substance of our discussions : “You’re in love with Ziad, right…” - I was in love in deed, and I was not afraid to say it, because it was a purely intellectual passion.

This gave me access to a completely different side of social life, dominated by political passions. While my relationship with the shopkeepers was dominated by the passions of the souk : curiosity and material interest. They told me things about the neighborhood, and I did not really listen to them. But when people from the neighborhood started coming to me also on the square, Ziad was weakened in his position, and quickly overtaken by events. He finally retreated to his village, and never agreed to get actively involved again in my research. My stay ended up in a very confuse situation, and I left to Sanaa three weeks before my flight.

…But nine months later I was back, because I really needed to understand.

When I came back to Taiz in 2004 for my second research, I decided

to reside in Hawdh al-Ashraf, hoping to notice the details in

between. So I stayed in that hotel overlooking the Square.

These two social places expressed very different viewpoints on

political issues, and this included different viewpoints on me and

my story in Yemen.

- For the shopkeepers, I was abused by the “tribal” mentality of the neighborhood.

- For the neighborhood, I was just a Westerner lacking the sense of honor and morality.

Happily, the square of Hawdh al-Ashraf was an endless source of

inspiration.

These are shuqat, rural workers who come to town to look

for work, in the first hours of the day.

And next to them, pupils of a private school waiting for their

bus.

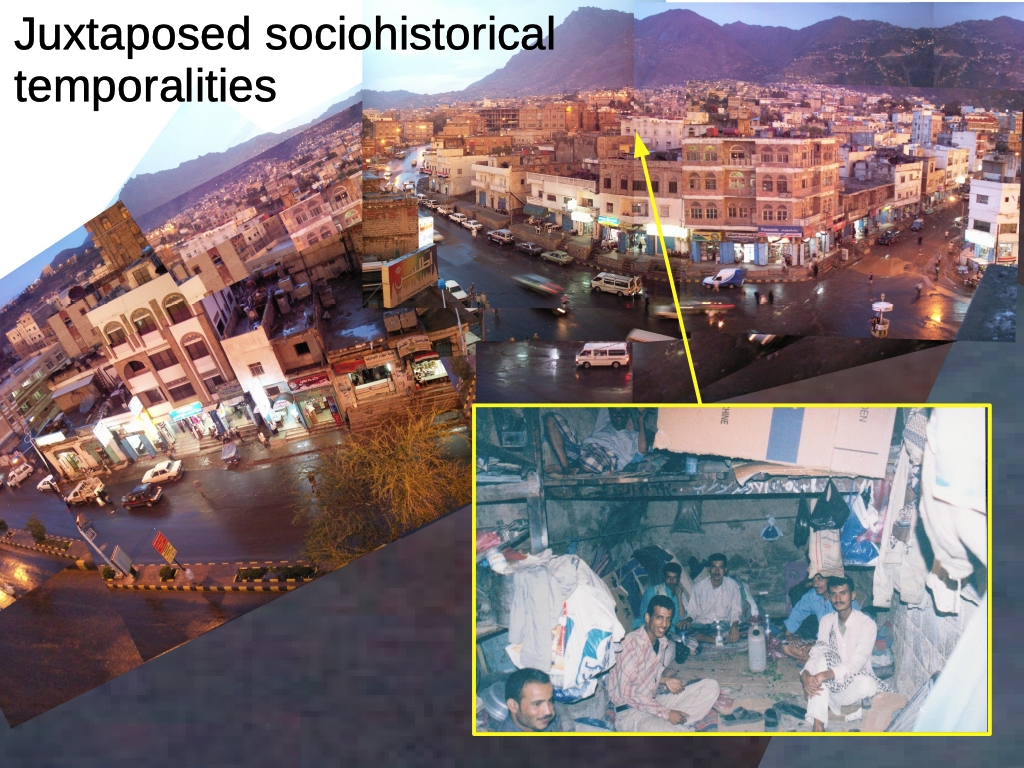

And then in the afternoon, young men from Jebel Saber, also

workers, who proudly chew qat in the dust.

They are maintained at distance by yet other workers / shuqat,

in the name of protecting the integrity of townswomen.

These are rural workers from Al-Qubbayta, who live and work as

bodybuilders inside Ziad’s neighborhood, right in front of his

house.

And this is Ziad’s younger brother Yazid, in 2004 during ramadan,

selling juices and samosas with the young neighbors. Yazid also

considers himself a shaqi, and he shows it on the square

in front of his own neighborhood.

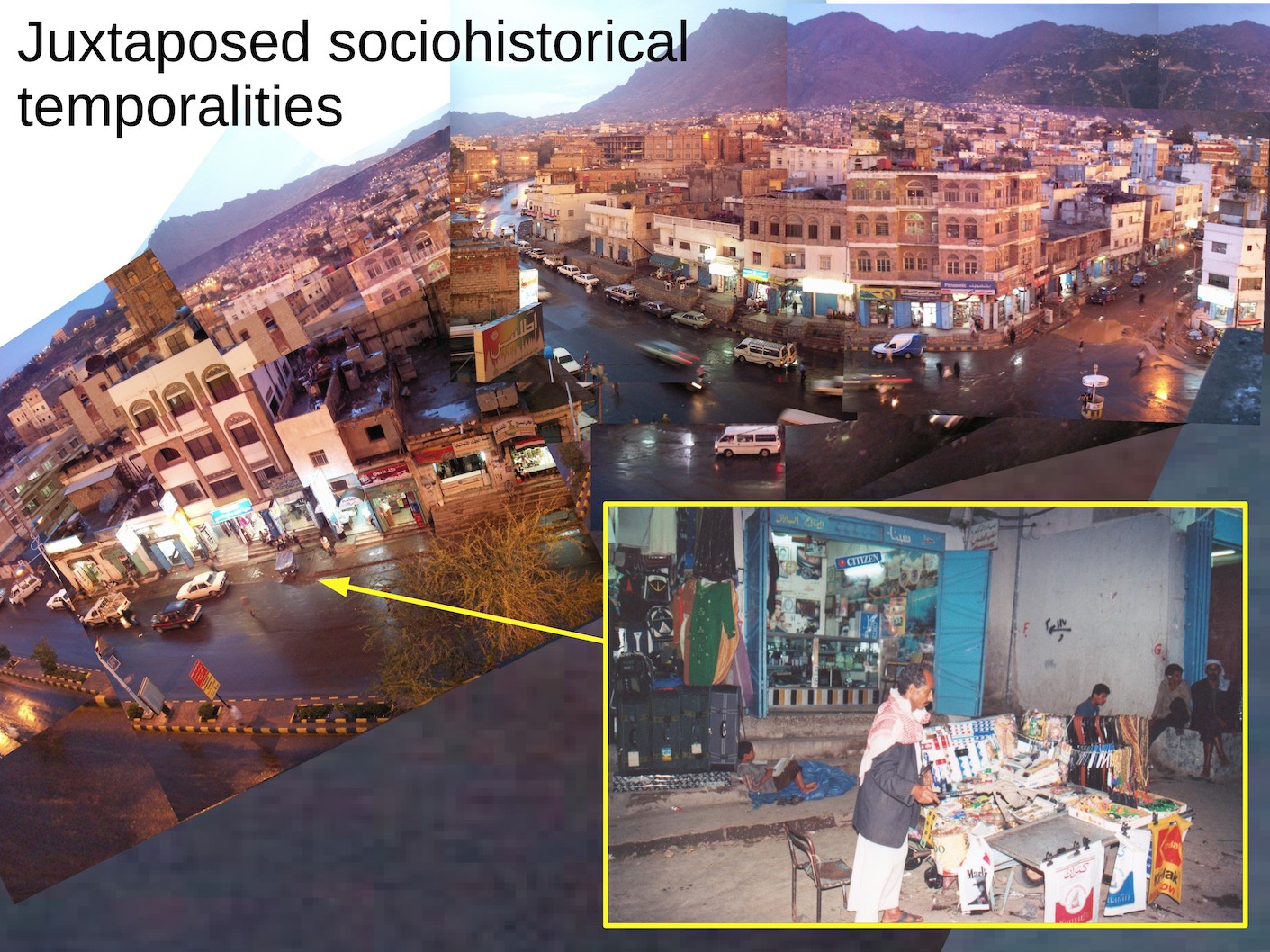

For this street-vendor from al-’Udayn, it is just the opposite. He

lives with his family in another neighborhood, and he comes to

Hawdh al-Ashraf every morning to work as a seemingly precarious

street-vendor.

These brothers from Qadas hold a grocery store on the Square, but

they sleep in a dukkan inside Ziad’s neighborhood.

A shopkeeper from al Abous, teasing a streetvendor from Shamir.

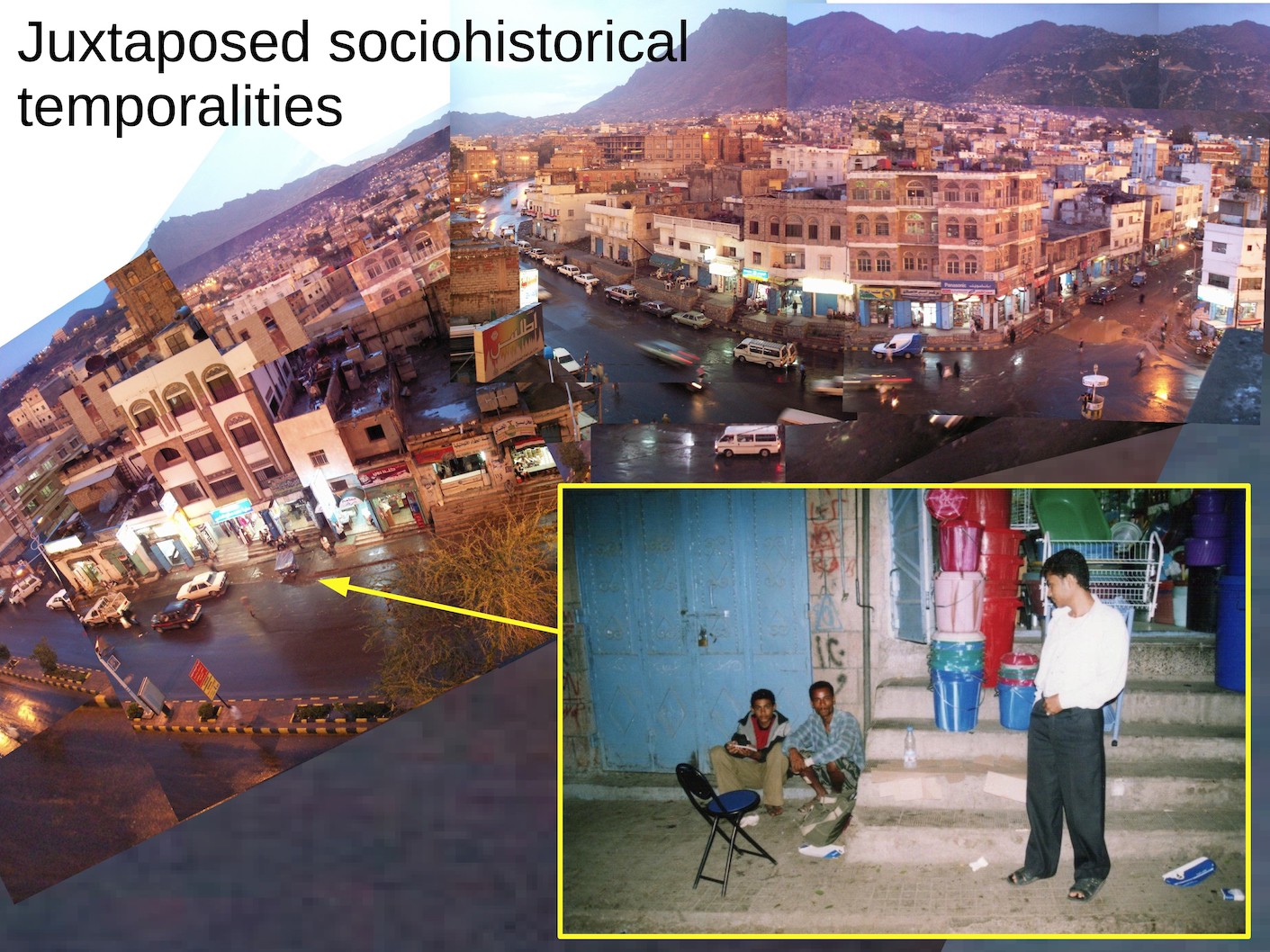

And in that same place, an engineer distancing himself from a

shaqi (who happens to be from town actually, “hiding” amongst

rural workers, for various personal reasons).

And that is the owner of the shopkeeper’s building

At the end of my third stay in 2006, I have already spent twelve months in Yemen, mostly in that place, looking for signs of domestic power in the public space, and studying the coexistence of sociohistorical temporalities…

And then on the day when I came back for my fourth stay, Ziad set

fire to the house of his family. He was the maths genius that I

encountered four years earlier, with whom I hoped to collaborate

initially, the reason for my presence in that place.

Until 2006, I regularly came and shared my theories with him. But

over the course of those years, he started to refuse corruption

and failed professionally. And then he failed in his wedding,

because he appeared to have a medical problem, and he never could

consummate the union, so he lost all social consideration.

Meanwhile his older brother Nabil started to have more and more

problems in the souk, and he died in a car accident. The

Municipality wanted someone from the family to take up his

position, but Ziad refused,

and the younger brother Yazid had always considered himself a shaqi,

so he didn’t have the shoulders to take such a job overnight. So

they sent Ziad to a mental clinic, hoping that he would change his

mind, but the electroshocks only destroyed him.

Already when I heard the news of Nabil’s death, while I was in France, I felt confusedly guilty. I had the strange feeling that my gaze was responsible for this tragedy.

For me until then, Nabil was the baddest guy on Earth : he was the Regime, the only person in Hawdh al-Ashraf that I did not consider identifying with. And I had my own reasons : at the end of my first stay in 2003, after Ziad’s retreat, Nabil supposedly tried to rape me… - it was during the night, the young neighbors hid me in an apartment, and then exfiltrated to the square… - And that is why I left Taiz ahead of time, it was more than I could handle. I never talked about it in any of my writings, but the image remained inscribed in my mind, it was part of that sociological representation that I had constructed (the red part of society…). Only last year in 2018, when the regime had totally crumbled and more than a decade after his death, I realized that Nabil was completely innocent of that. And when I go back to my fieldnotes now, it is obvious that the whole society collaborated to convince me of this - neighbors and shopkeepers alike. I think that they behaved this way to protect the inter-subjective relationship that we had… I did not understand all that at the time, but four years later, on the day when Ziad burnt the house, nobody mentioned the coincidence with my arrival. People on the square remained silent, and behaved with me as if nothing happened. Which meant that they knew, somehow… This was a turning point in my research, because it confirmed in front of all an intuition that I had, that the square was a cybernetic system: something with much more collective intelligence than I initially conceived. I decided to listen to this intuition, and try to change my theoretical approach to assume my responsibility, even if that meant that I would have to retreat from Yemen. I took Islam in my luggage back to France, and I did retreat from the country two years later, but keeping a true relationship with Ziad’s neighborhood and his family, especially his younger brother.

Yazid entered politics a few years later : he is the one who

took the responsibility to throw me out… It is a conflictual

relationship, but a true one.

And Yazid is still in Hawdh al-Ashraf today, he stood firm through

the revolution and the war. We’re still in touch, I think he does

some good work, and that relationship means a lot to me.

For me and for Yemen’s future, I insist that relationships are more important than theory. Still, I’m going to tell you how I adapted intellectually to this new situation. That was a relational reframing, and a theoretical reframing came along with it.

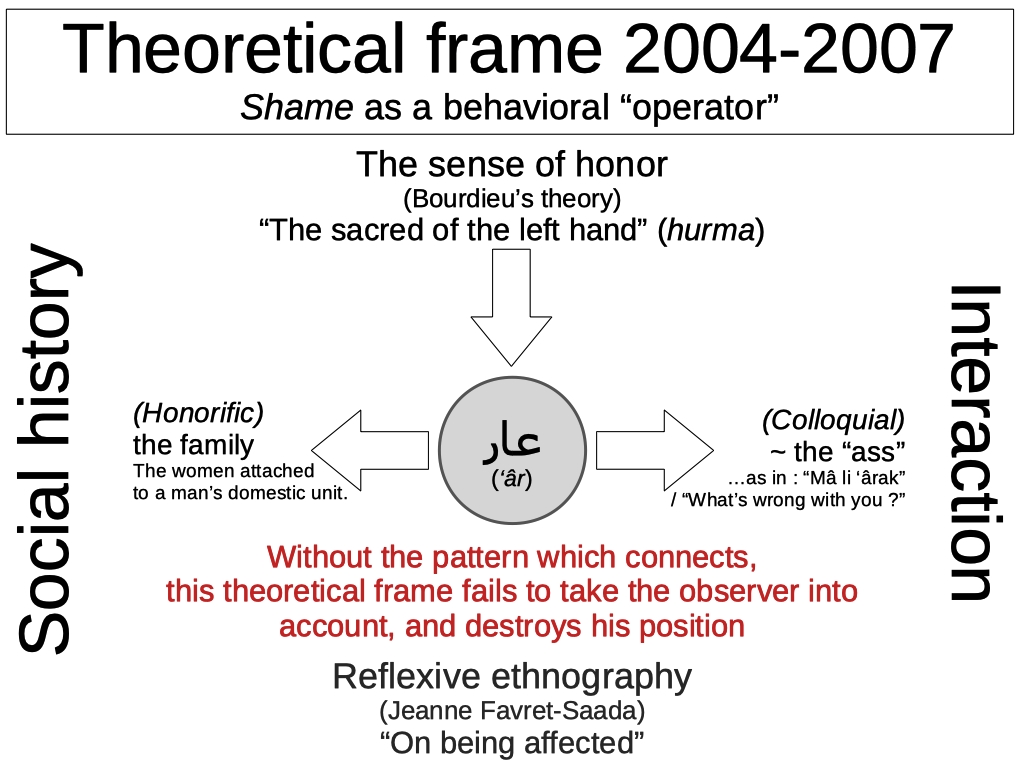

Before islam, this was the theoretical frame of my research. My

ambition was to understand interactions in relation to social

history, and to bridge between the macro and micro dimensions of

social life. Since I am not a woman, I could not see through the

domestic space of my interlocutors, and my information were very

limited on their family history. Still I gradually got better at

“catching the shame” of each actor, which means understanding

where he speaks from.

But paradoxically, I did not know “shame” for myself : I did

not really feel the weight of my presence in society, and did not

understand my own story. My research was haunted by questions of

abuse, distrust and anonymity, which resonated in the

socio-political climate of the time. But the more I persisted in

this academic discourse, the less I knew how to keep things in

perspective, between the personal and the collective urgency. And

this was my intellectual preparation to what Muslim theology calls

shirk (or idolatry), I think - but I won't get into

details here.

Anyway after 2007, the rules of the game changed. As I retreated from the Square and lowered my ethnographic gaze, I had a closed set of material, with no hope of further exploration. So I started to analyze those past misadventures with a fresh perspective, as some kind of tragicomedy.

Back in France in early 2008, I formulated this “theorem of

ethnographic enchantment”. - that I later used to shed light on

the specific identity of Taiz For the enchantment of the observer,

you need to have :

- one Yemeni who strikes a pose as an indigenous ;

- and another one who informs him, using Western categories.

This pattern is actually much more general, in the relationship

between Europe and Islam since medieval times. It has to do with

the fact that Islam was a meta-context of the European history of

ideas. Since the end of the middle ages, European subjectivity was

constructed on Greek intellectual tools that were extracted from

the ecosystem of medieval monotheism. Therefore today, the Muslim

who looks at the Westerner cannot be the one who reads his books.

And the Muslim who reads the books of the Westerner is not

supposed to look at him in the eyes. There is a kind of reticence

on both sides.

Anyway, I started to spot this same pattern everywhere, as I gradually recovered the memory of my own story.

For instance, this is a quick visual summary of my first fieldwork

in 2003.

- The circle in the middle represents the moment when Ziad faced a small-scale Arab Spring in his own neighborhood, and suddenly everybody came to talk to me. Clearly in this context, the Yemenis put me in a double bind, by making me believe that Nabil wanted to rape me.

- But that was a response to the double bind that I put them in : the sheer presence of a flesh and blood Westerner, in the context of modernity (circle on the left).

- That is why I started to analyze social behaviors as sexual behaviors, this was the only conceivable explanation (that is the circle on the right…). Plus in order to start writing, I had to escape this double bind and remain connected to this society from afar. That was the only solution.

But when I returned to Taiz, that belief impacted my social behavior, and it was a handicap. All occasions of sociability were spoiled by my sheer presence. And that is why I didn’t get far from Hawdh al-Ashraf, and ended up on the sidewalk with the shuqât. In such a condition, I could hardly presume to give a representative vision of Yemeni society.

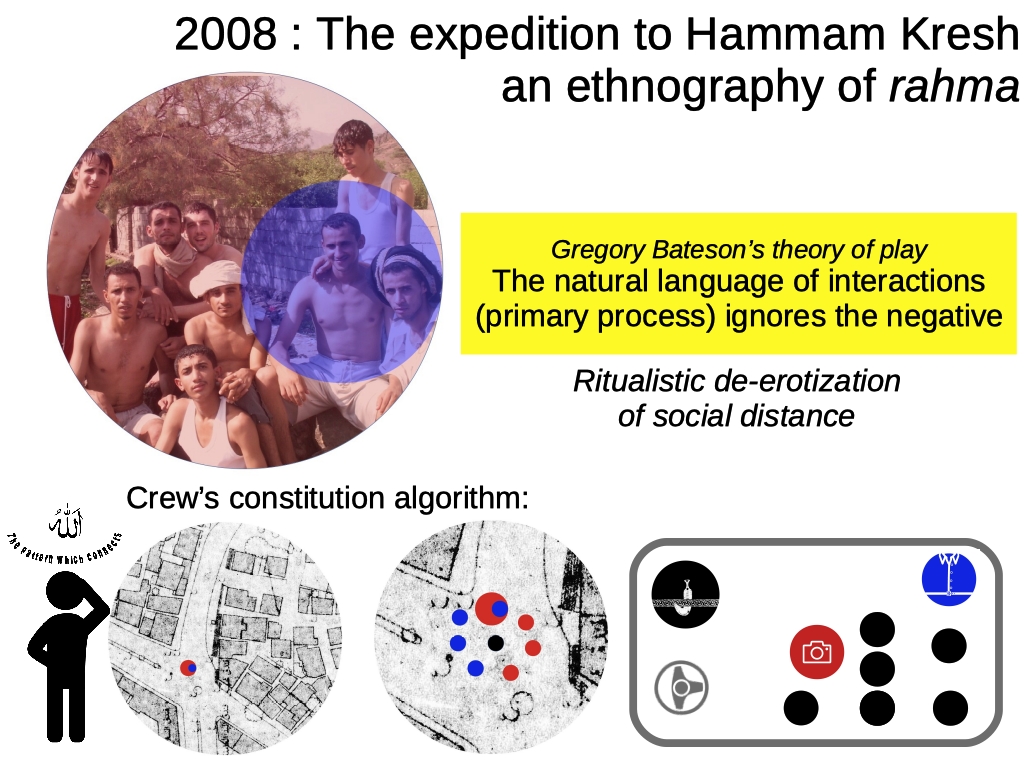

It was in September 2008, one of the few graceful moments that I lived in Yemen before I retreated. During ramadan, the early morning is a time of social exploration for the youth, when everyone else goes to sleep.

This is the story of how we managed to get on a bus that we rented collectively,

- with people from the square and people from the neighborhood,

- people who knew each other and people who just happened to be there,

- people who knew my story and people who did not…

How the crew aggregated against all odds, creating a sufficient trust between its members, so that we could finally embark to the hot sources of Hammam Kresh. For me, it was probably the first time since 2003 that observation and participation went together again.

And the funny thing is how it all started : Coming out from the masjid on the square, one of Ziad’s neighbors took the cellphone of a shopkeeper, and he said to him : “I’ll give it back to you when you come with me to Hammam Kresh…”. So, the original intrigue was a blatant situation of abuse. But paradoxically enough, this is what allowed for all the participants to have a good feeling about this expedition.

To understand this paradox, Gregory Bateson’s theory of play is very helpful. In the natural language of interactions, there is no negation. You cannot say : “I am not abusing you”. All you can do is to speak of an abuse in a context that makes it sound unreal. And this is why ritualized vulgarity is commonly used as a way to de-eroticize social distance. This kind of observation helps us to understand how Yemeni society fits together, and not just where the divisions supposedly come from.

Enrolling the Westerner’s gaze can be part of the same strategy.

The shopkeeper’s reaction when I took a picture is very telling,

because he finds himself isolated in his outrage, and it is very

funny.

It is all a question of context actually. And that is the problem that I had with the reception of this research. By 2008, the misunderstanding was over in Hawdh al-Ashraf, broadly we all understood the story. But in the academic arena, it is actually much harder to address these issues in depth.

That is why I mentioned the history of ideas. I think we can no

longer ignore epistemology in the larger pattern of the

relationships between Europe and Islam. Studying the reception of

Gregory Bateson’s idea in the Middle East is one way to understand

what is at stake.

Thank you.